Funding health expenditures is a major source of tension in the Canadian federation. Comprising between 30-50% of annual provincial budgets, healthcare is the largest single expenditure for provinces and territories. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the sustainability of health expenditures was under increasing pressure from an aging population. The pandemic has added further strain. Provincial and territorial budgets need help, but federal-provincial fiscal arrangement in healthcare have undergone few changes since 2015. The Canada Health Transfer (CHT) is the largest federal transfer, totalling $42 billion in 2020-21. This policy brief will summarize the history of CHT, review current challenges to CHT, and discuss possible policy solutions and areas for further study.

To encourage the creation of a nationwide Medicare program, the federal government offered cost-sharing grants to provinces beginning in the 1950s and 60s (Béland et al., 2017). The Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act of 1957 guaranteed all provincial governments 50-50 cost sharing if they adopted universal hospital coverage under a set of national standards. The federal Medical Care Act of 1966 offered cost-sharing to all provincial governments that agreed to extend universal coverage to physician services. The provinces and territories that received the federal health transfers agreed to comply with four core principles: public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, and portability (a fifth principle, accessibility, was introduced by the Canada Health Act in 1984).

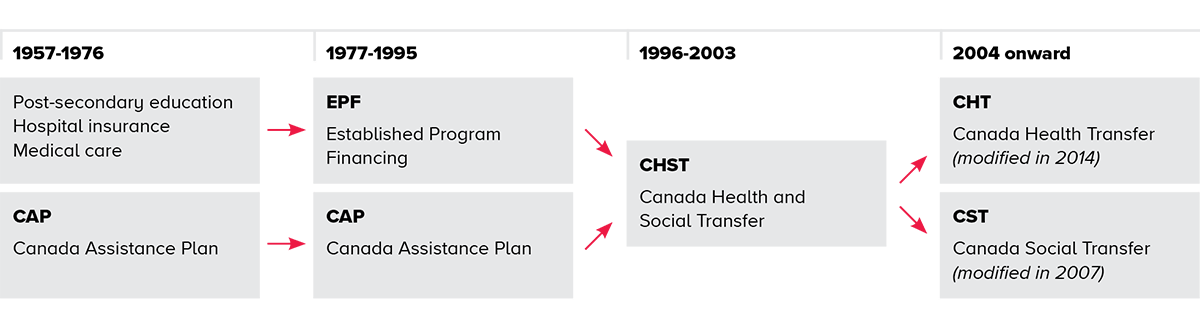

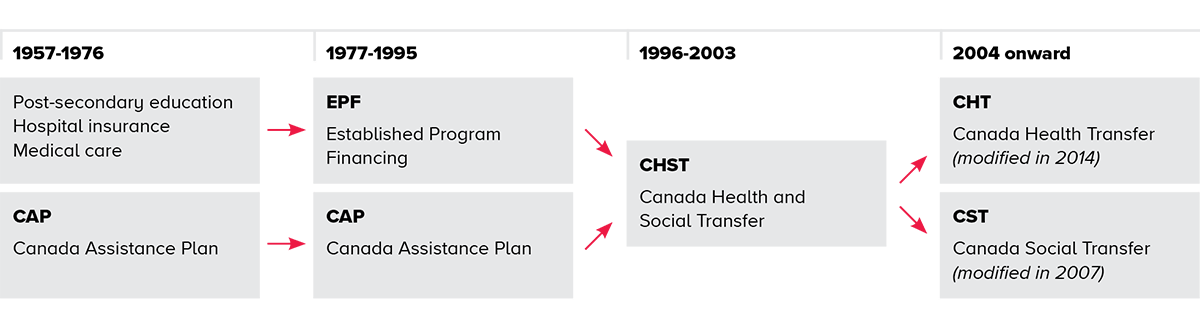

In 1977, the Established Program Financing (EPF) block transfer was introduced to replace the cost-sharing grants for healthcare and post-secondary education. EPF was made up of roughly equal parts cash and tax point transfer. The tax point transfers were 13.5% of federal personal income tax and 1% of federal corporate income tax. In 1995, EPF was replaced by a block grant called the Canada Health and Social Transfer. In the same year, the federal government implemented major cuts to the total amount of cash transfers made to provinces and territories.

In 2004, Prime Minister Paul Martin divided the Canada Health and Social Transfer into the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) and the Canada Social Transfer (CST). Like previous programs, both the CHT and CST included a cash transfer and the value of the tax points transferred in 1977. The cash portion of the CHT was indexed to economic growth. Tax points generated provincial revenue in line with the tax room actually taken up by the respective province and its economic growth. The CHT and CST were allocated on an equal per capita (cash and tax point) basis. Because the cash transfer was calculated as the residual between the total gross amount of the transfer and the value of the income tax points, provinces with smaller per capita income tax bases received larger cash transfers than those with above average tax bases (Béland et al., 2017; Marchildon & Mou, 2014).

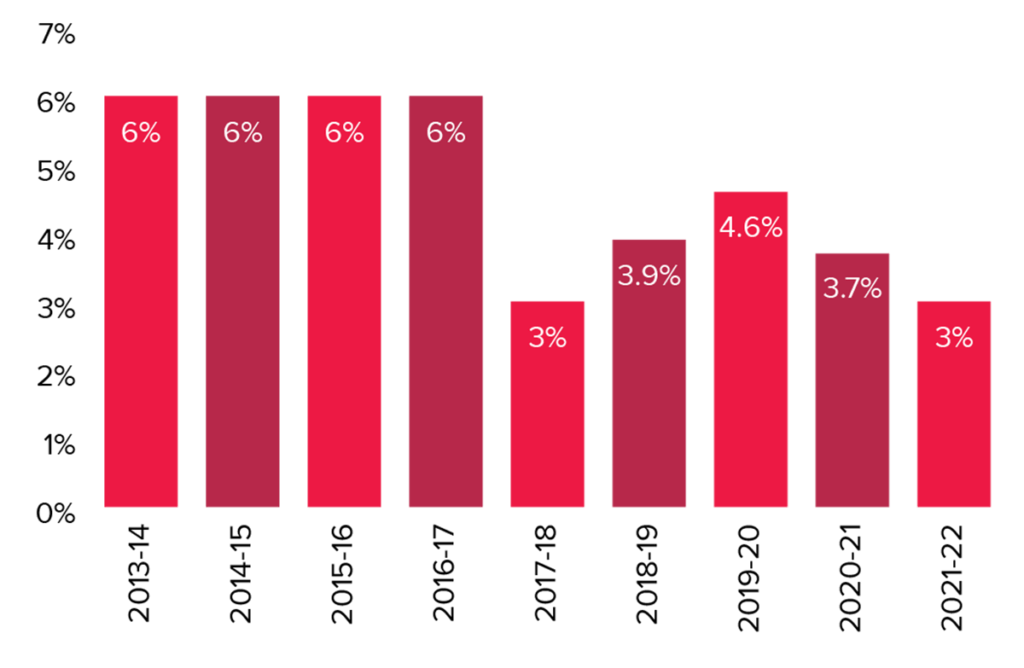

After the 2004 First Minister’s meeting on the future of healthcare, the Liberal government produced A 10-Year Plan to Strengthen Healthcare. In this plan, the federal government committed to increasing the cash portion of the CHT by 6% annually from 2006-07 to 2013-14. The 10-year plan restored certainty and stability to provincial and territorial health systems.

In 2011, a majority Conservative government led by Stephen Harper came to power. In December 2011, Prime Minister Harper announced that starting in 2017-18 the cash portion of the total CHT would grow in line with a three-year moving average of nominal GDP, with a floor of 3% per year. In 2014-15, the Harper government changed the allocation of the CHT transfer from an equal per capita total transfer (cash and tax point) to an equal per capita cash transfer formula. This change followed the 2007 change in the allocation of the CST to an equal per capita cash basis. Under the new formula, all the provinces and territories receive the same per capita amount of CHT and CST cash transfers, regardless of their tax point transfer value. These changes mean that although the per capita amount of CHT and CST transfer grows with the Canadian economy, poorer provinces and territories receive a smaller share of CHT compared with their share under the Martin government’s allocation formula (Marchildon & Mou, 2014). Figure 1 summarizes the evolution of the federal health and social transfers.

Source: Béland et al. (2017)

In 2015, a majority Liberal government led by Justin Trudeau came to power. On December 19, 2016, federal and provincial finance and health ministers met in Ottawa to negotiate a new health accord. Premiers pushed for a 5.2% annual escalator to the CHT from 2017-8 on, arguing that this rate of growth was required to cover the cost of an aging population. The federal government offered a 3.5% annual escalator instead stating that this growth rate is already higher than combined GDP growth, inflation, and health cost growth in the past five years. Multilateral negotiation broke down. Through one-to-one negotiations, the federal government struck bilateral deals with every province and territory. Ultimately, the CHT annual escalator was kept at the same level as under the Harper government – total CHT cash transfers will grow in line with a three-year moving average of nominal GDP, with a floor of 3% per year.

Figure 2 shows the annual growth rate of the cash portion of the CHT, demonstrating that the annual escalator was between 3% and 5% after 2017-18, lower than the previous 6% rate from 2006-07 to 2016-17.

Source: Government of Canada (2021)

Bilateral agreements struck in 2016 offered an additional $11.5 billion in the 10 years starting from 2017-18 targeted to improve home and community care, mental health and addiction services. The 2017 federal budget confirmed that the funding included $6 billion for home care, with $1 billion set aside for home-care infrastructure, and $5 billion dedicated to mental health services (Government of Canada, 2019). The 2017 budget also confirmed the first five years of funding allocation: $0.3 billion for 2017-18, $0.85 billion for 2018-19, $1.1 billion for 2019-20, $1.25 billion for 2020-21, and $1.5 billion for 2021-22 (Government of Canada, 2017).

From 2017-18, this $11.5 billion will be allocated equally on a per capita basis, which for example will amount to an additional $4.2 billion for Ontario and $2.52 billion for Quebec over 10 years (Government of Canada, 2019). As a condition of receiving this additional federal funding, recipients all agreed to report on 12 common performance indicators in mental health and home care services, and report how the funds are spent, over and above existing programming. Among the 12 common indicators, it is expected that wait times will improve for children and youth accessing mental health services, and that increased home and community healthcare supports will lead to a reduction in the number of patients in hospital.

Conditional, special-purpose federal health funding is an interesting development in fiscal federalism that can be traced back to the 2002 Royal Commission on the Future of Healthcare in Canada, led by Roy Romanow (the Romanow Report). The Romanow Report recommended that federal health transfers be designed to increase accountability to taxpayers (Marchildon & Mou, 2013). Following the recommendation, the Health Council of Canada was established to develop national benchmarks for quality of care and regularly assess healthcare system performance.

A renewed focus on accountability led to the Wait Times Reduction Fund. In 2004, The 10-Year Plan to Strengthen Healthcare committed to reducing wait times in five priority clinical areas: cancer radiation therapy, cataract surgery, cardiac care, joint replacement, and diagnostic imaging. The federal government provided $5.5 billion to the Wait Times Reduction Fund over ten years beginning in 2005-06 (Government of Canada, 2005). In December 2005, all provinces and territories publicly committed to a set of common wait time targets and committed to reporting progress in meeting these targets (Government of Canada, 2012).

Following the introduction of the Wait Times Reduction Fund, there was a substantial reduction in wait times in the five priority clinical areas. By 2010, about 90% of Canadians received radiation therapy within the recommended clinically acceptable wait times and about 80% of Canadians received other priority procedures within the benchmark time frame (CIHI, 2013). However, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) notes that wait times for many other procedures have not improved due to rising demand (CIHI, 2013).

The federal government’s $11.5 billion commitment for mental health and home care is conditional, special-purpose health funding. By attaching conditions to funding, the federal government is able to influence operations and uphold national standards. When introduced, the Health Minister, Jane Philpott, stated that provinces have enjoyed 12 years’ substantial increases in health transfer but health outcomes, including wait times, have seen few meaningful improvements (Tasker, 2016). Conditions aim to incentivize innovation, extract efficiency and improve health outcomes.

The accountability mechanism in the special funding on mental health and home care is limited to reporting requirements. There was no funding scale-back or penalty for provinces or territories that fail to improve health outcomes. Therefore, the conditional funding on mental health and home care services, like the Wait Times Reduction Fund, has little real power to hold the provinces and territories to account for health outcomes. Yet, the use of conditional funding, in lieu of an increase in the annual escalator of CHT, sends a signal that the federal government seeks to uphold national standards in priority healthcare areas.

After the pandemic, the fiscal gap between Ottawa and provincial/territorial governments will likely widen. The Parliamentary Budget Office’s recent fiscal sustainability report projected that the federal government’s debt-to-GDP ratio will decline while the debt-to-GDP ratio of the provinces and territories as a group will grow in the next decades (PBO, 2020). Only three provinces — Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia — are on a fiscally sustainable path. The other provinces and territories face a fiscal gap of varying degrees. When the pandemic ends, fiscal arrangements between the two order of government will need to be rebalanced. Below I will discuss two policy proposals at the centre of this debate.

One proposal is to reallocate federal tax points to provincial/territorial governments, a point Globe and Mail columnist John Ibbitson argued for in November 2020 . Later this year, the Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations Commission plans to publish a backgrounder reviewing Canada’s experience with tax point transfers and an analysis of the pros and cons of a tax point transfer in lieu of increases in federal transfers. Under tax room reallocation, the federal government would relinquish some tax points from income tax or sales tax, leaving the provinces and territories to occupy the tax room. If such a change was implemented, wealthier provinces such as Alberta and Ontario would be able to generate more tax revenue from the same tax points and use this to strengthen their health services, and such a model would exacerbate the problem of horizonal health care inequity.

A second policy proposal is to reform CHT’s allocation formula. All provinces are facing rising health costs and aging populations, but some have more older residents than others. This means different provinces/territories have differing health service needs. To reduce inequities among the provinces and territories, the federal government could modify the CHT allocation formula to account for their different demographics. The Equalization program is constitutionally established to address differences in both revenue and expenditure needs with a goal to ensure reasonably comparable levels of public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation across provinces. Reforming the equalization formula to accommodate differing demographics would be politically challenging. An age-adjusted allocation of CHT may be more generally accepted and widely understood than adjustments to Equalization (Marchildon & Mou, 2014; MacNevin, 2004). An age-adjusted per capita allocation of CHT would mean the four Atlantic provinces, British Columbia, and Quebec would receive a larger share of CHT than under the current equal per capita allocation. Alberta would receive a lower share of CHT (Marchildon & Mou, 2014).

In the current context, the most politically feasible policy solution is to maintain the status quo. In other words, the federal government would continue using conditional, special-purpose health funding to implement new programs in areas of provincial responsibility. Provinces and territories always want more unconditional financial support from the federal government to address the vertical fiscal imbalance between their expenditure responsibilities and their revenue raising capacity, while Ottawa prefers to use conditional funding to incentivize new programs and/or compliance with national standards. With the signing of bilateral agreements on mental health and home care, the federal government might use a similar approach to entice the provinces to join the national pharmacare or long-term care programs that were promised in the 2020 Throne Speech. In the long run, at the urging of some provinces, the federal government may consider an age-adjusted per capita allocation for CHT to address provincial and territorial differences in health expenditure needs.

References

Béland, B., Lecours, A., Marchildon, G.P., Mou, H, & Olfert, R. (2017). Fiscal federalism and equalization policy in Canada: Political and economic dimensions. University of Toronto Press.

Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI, February 2013). Wait times for priority procedures in Canada, 2013. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/wait_times_2013_en.pdf

Marchildon, G.P., & Mou, H. (2014). A needs-based allocation formula for Canada Health Transfer. Canadian Public Policy, (40)3, 209–223.

Marchildon, G.P., & Mou, H. (2013). The Conservative 10-year Canada Health Transfer plan: another fix for a generation? In C. Stoney & G. B. Doern (Eds), How Ottawa spends, 2013 – 2014: The Harper government: Mid-term blues and long-term plans (pp. 47 – 63). McGill-Queen”s University Press.

MacNevin, A. S. (2004). The Canadian federal-provincial Equalization regime: An assessment. Canadian Tax Paper, No. 109. Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation.

Government of Canada (2017). Building a strong middle class. Federal budget plan. https://www.budget.gc.ca/2017/docs/plan/budget-2017-en.pdf

Tasker, J. P. (December 19, 2016). Ottawa, provinces fail to reach a deal on health spending. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/health-accord-meeting-1.3903508

This work is part of a proposed Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations Commission – an independent team of academic experts and policy practitioners from a variety of disciplines across the country, brought together to make research-based recommendations for the reform of fiscal relations among the federal, provincial and municipal governments. The Canada West Foundation is a member of the steering committee for the Commission. For more information visit the IFRC homepage.